“There are no leaders fit to rule

We’re all half saint, half bloody fool”

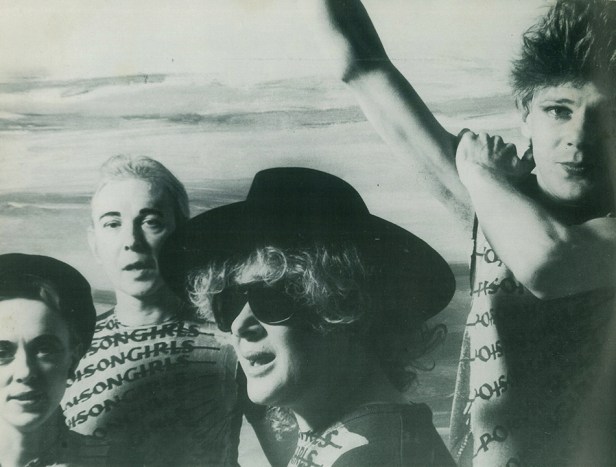

Poison Girls

15/01/25 repost by Rich Cross at The Hippies Now Wear Black 8 Comments via thefreeonline at https://wp.me/pIJl9-Fyo Telegram https://t.me/thefreeonline

‘ Vi Subversa, born Frances Sokolov on mid-summer, June 20, 1935, in London, England, was the only child of Sarah and Sydney Sokolov, who were part of the Jewish immigrant community in working class London’s East End. Vi was a blitz kid, growing up during World War II, which contributed to her rebellious anarchist feminist, anti-authoritarian perspective’.

Vi Subversa, died on 19 February 2016, aged 80, after a short illness, she will always be remembered as one of the the most distinctive figures in the first wave of British anarchist punk.

Poison Girls, the band that she fronted, wrote with, recorded with and performed with, were as important a catalyst in the formation of the subculture that became known as ‘anarcho-punk’ as were Crass.

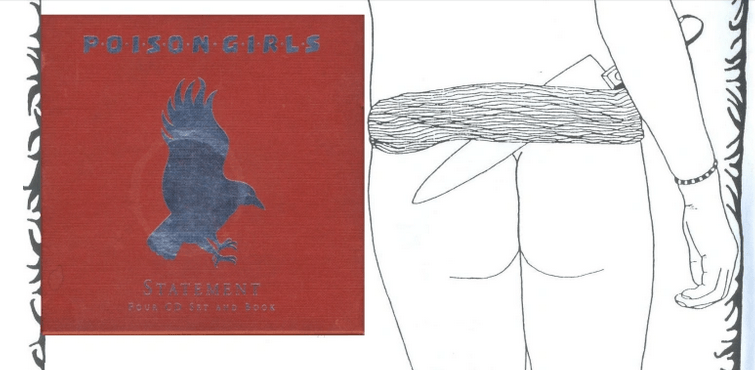

THE FIRST BOOK length study of the work of Poison Girls, by Rich Cross, will be published this November 2025 by PM Press. https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=1829

The fact that these two bands emerged independently, worked closely together and then evolved in sharply different directions is the reflection of many different influences, but the clarity of vision which Subversa was able to articulate so effectively played a key role in presenting the shifting subversive perspectives of Poison Girls..

Born Frances Sokolov in 1935, she had enjoyed a successful career and brought up two young children, Pete Fender (born Daniel Sansom, 1964) and Gem Stone (born Gemma Sansom) before the arrival of punk in the mid-1970s.

She had played a part in hippy culture but had been disenchanted both with its failure to make political headway and also the peripheral status that many women within hippy culture found themselves occupying.

Prior to the onset of punk, Vi had been involved with counter-cultural art happening The Body Show, where she made her singing debut in 1975 at the age of 40, an experimental, semi-improvised cabaret which attracted a great deal of censorious and outraged press attention (which focused on the apparent, but entirely illusory, nudity in the show), but which had longer significance as a formative project in the formation of Poison Girls.

One of the fallacies of the ‘story of anarcho-punk’, often recounted by members of Crass and some of their biographers, is that the catalyst bands of the movements were formed by political innocents; inexperienced activists who fumbled in the direction of anarchism through trial and error and largely in the interest in rebuffing the attention of the recruiting sergeants of the political right and hard left.

Lance D’Boyle: English anarchist drummer; punk rocker in Poison Girls Lance d’Boyle of Poison Girls dies

It was always a wholly unconvincing (if suitably romantic) account of these activists’ ‘discovery’ of the world of anarchism, but in the case of Poison Girls it was patently untrue.

Like Lance d’Boyle, Vi Subversa had long associations with the organised British anarchist movement.

Subversa arrived at the intercession of punk as a single mother of growing children with years of political engagement and knowledge behind her

Decades before the punk explosion, she had street-sold the anarchist paper

Freedom, taken part in libertarian initiatives and anti-nuclear campaigns and been a member of different anarchist groups, following the evolution of the post-1968 libertarian left. Subversa settled down with the British anarchist activist, illustrator and author Philip Sansom (19 September 1916-24 October 1999) with whom she had two children: Pete Fender and Gem Stone.

Sansom had been a regular at London’s Speakers’ Corner (arguing for any number of libertarian causes); had been an infrequent editor of Freedom and in the final year of the Second World War had been jailed (along with other anarchist comrades) after being found guilty of “conspiring to cause disaffection among members of the armed forces”.

Subversa had been an active, literate (and critical) participant in the early years of the first wave of British feminism, and arrived at the intercession of punk as a single mother of growing children with years of political engagement and knowledge behind her. Hardly the story of an anarchist ingenue.

By 1977, Subversa and the newly Poison Girls (Richard Famous, Lance d’Boyle, and the first in a long line of different bass players) were living and working in Brighton. Members of the band played a key role in setting up new punk venue The Vault and the first breakthrough punk fanzines in the city.

From the very beginning, Subversa stood out, because of her age and her sex. In a punk culture which heralded a ‘year zero’ approach to youth and a suspicion to any hangovers from the hippy era, she asserted her determination to part and parcel of this new oppositional movement without a hint of apology or self-doubt. Fronting her band as an older woman doubled the challenges she faced down from those in the scene who saw her as an interloper.

What made Subversa such an inspirational figure within the alternative punk scene was not simply the fact of her presence (an older women, of comparable age to the parents of the majority of those in the audience), but its manner. She remained gloriously unrepentant and unapologetic: completely convinced about her right to be there, and determined to be accepted as an equal contributor to this latest wave of counter-cultural opposition.

From their earliest days, the group championed an independent approach to their musical and cultural practice. The first vinyl release by the band, a joint release by Small Wonder and Poison Girls’ own Xntrix label, demonstrated that commitment to a DIY ethos, but it showcased much more besides.

The band’s initial take on the ‘punk idea’ produced some innovative musical thinking, but foregrounded Subversa’s own distinctive vocal style: the rich timbre, the gravelly undercurrent, the understated power, the evident passion.

Extraordinarily, the other side of the twelve-inch featured The Fatal Microbes, fronted by Honey Bane, and featuring Subversa’s children Gem Stone and Pete Fender. What better rebuttal could there be of what Richard Famous dismissed as the ‘crap’ of the generation gap than having a mother, daughter and son collaborate on a shared punk record?

And from the perspective of the younger generation, how many entrant punk musicians recorded records ‘with their Mum’? It was the beginning of a long period of collaboration that would see mother and children share the stage time and again (whilst securing the autonomy of their respective independence – and making no direct reference to their familial connections).

Fronting her band as an older woman doubled the challenges she faced down from those in the scene who saw her as an interloper

The first conversation I had with Vi Subversa and Poison Girls was when the band played in Exeter in October 1981 as part of the ‘Total Exposure’ tour. The first thing she said to me? ‘You play in a local punk band, right? Can you play a support slot in an hour?’. That simple; that direct; that open. Poison Girls had been appalled by the soundcheck of the icky, inappropriate club act that the local CND organisers had lumbered them with. (‘What has ten legs but no kneecaps?’, a seething Tony Allen asked the audience from the stage later.

‘A crap band that tells too many Irish jokes.’) Our band couldn’t do the gig (to my eternal regret), but Poison Girls readily agreed to be interviewed before the show. So three of us (an eighteen year old, a seventeen year old, and a fourteen year old) were given an uninterrupted 45-minutes backstage to quiz the band about their politics, practice and aspirations.

It was (without a hint of hyperbole on my part) a revelatory experience. Up to that point in my life, no adult outside my family had ever spoken with me face-to-face before about huge, world-changing ideas without coming over as hugely patronising (or, like my WRP politics lecturer, unhinged).

Vi, Richard and Lance (with Tony Allen chipping in at points) spoke clearly, persuasively and passionately without a hint of condescension or of compromise. Subversa, in particular, was razor-sharp, convincing and compelling.

That conversation (which ranged over questions of anarchism, feminism, radicalism and age, abortion, the possibilities of punk and hippy, the Bomb, and about resistance and resilience) was one of the most significant, exciting and inspiring political dialogues of my teenage years.

And Poison Girls played an absolute blinder that night. They had me at the opening bars of Statement (the song began as a pre-recorded intro tape blasting through the PA; with the band gradually taking over a live performance on stage as the song progressed – a Brechtian technique for dispensing with rock’n’roll hubris that I’ve rarely seen bettered).

There was a great sense of resilience surrounding Poison Girls. Despite (and, of course, because) of the band’s opposition to machismo, thuggery and ugliness of discrimination, their gigs frequently became target for the attention of bully-boys.

The band’s live performances could be marred by violence; often these could be serious incidents involving assaults on the band as well as other members of the audience. Some such events, such as the controversial ‘anti-fascist’ assault at one of the early Crass and Poison Girls gigs at London’s Conway Hall, and both band’s horrific experiences at the 1980 Stonehenge festival are well recorded.

But sporadic and organised acts of violence were an unwelcome recurrent feature of an unfortunate number of Poison Girls shows. Subversa’s position as frontwoman of the band put her in the clearest jeopardy in such situations, and, as a fortysomething woman in the midst violent mayhem engineered by teenage and twentysomething men, she exhibited impressive levels of bravery.

In the face of attempts at intimidation, she didn’t buckle; she bristled; outraged at the attempt by anyone to silence her.

Subversa’s vocal style was extraordinary and genuinely distinctive, ranging from the full-on assault, through the textured and melancholic, to the whispered and cracking.

It was a voice that could intoxicate with its righteous passion; its sense of bitter regret; and its revelation of vulnerability and self-doubt. No-one else in the scene sounded like Vi Subversa; and, very wisely, no-one else tried to.

The band’s first full-length release Hex was an early wave punk record almost without parallel

Although the band’s relationship with the music press developed along much more productive lines than that attained by Crass, Poison Girls did not take criticism lying down. While Crass responded to the poisonous dismissals of Bushell and Parsons through the musical vitriol of Happy Up Garry/The Parsons Farted, Subversa’s response was, on one famous occasion, more direct and personal. Music journalist Paul Morley had made caustic and deeply unpleasant comments about Subversa’s appearance (the band were convinced he’d been in the bar for the entire set).

When Subversa heard he was in the Music Machine in Camden some weeks later, she went looking for him – and found him in the bar, where, Richard Famous recalls: ‘he had his tongue down some poor girl’s throat (he was supposed to be reviewing that gig too).’ Whether it was the loud volume in the venue, or Morley’s attempts to feign disinterest, it was clear that conversation was pointless.

In the circumstances, Subversa decided that a firm slap around the face would deliver a suitable rebuke. ‘He entered the Poison’s mythology as Mauled Poorly, and Vi got a tad of respect all round’, Famous remembers. ‘He dined out on that story for years, and incidentally when Hex came out he gave it a good review (and sort of apologised too).’

The band’s first full-length release Hex was an early wave punk record almost without parallel.

As well as providing further space for Vi Subversa to demonstrate her distinctive vocal talents, and the band to further explore their own musical style, what made Hex stand out was its lyrical preoccupations.

Subversa presented an exploration of the alienation and misery women experienced in the home; of the crushing expectations of narrow gender roles; and of the quiet horrors that awaited wives and mothers in the ‘normality’ of the nuclear family.

‘Is it normal? Is it normal? Is it just another day? Have you emptied out the washing? Have the kids gone out to play?’, asked Subversa, in anger and desperation.

It was not the kind of subject matter that interested many other early punk lyricists, and for many of the young punks listening to the record provided a completely unexpected perspective on the world of home, family and the lives of their parents.

Follow-up release Chappaquiddick Bridge saw the band broaden its political perspectives, to address the contemptible arrogance of unconstrained political power (typified by the ugly metaphor of the Chappaquiddick Bridge scandal) and restate its broader anarchist principles.

The album’s unlisted intro and outro track became one of the band’s most recognised (and quoted) songs.

State Control and Rock’n’Roll focused the band’s attention on the exploitation, cynicism and co-option of the music business; a theme that would continue to intrigue the band in the years to come.

If State Control showed the band’s mischievous, witty side, the accompanying Statement flexi was the boldest declaration yet of the band’s anarchist intent.

Voiced with spine-tingling sincerity and commitment by Subversa, Statement railed against the inexorable, destructive, all-consuming power of the war state and the band’s fulsome and absolute rejection of it.

‘I denounce the system that murders my children’, raged Subversa. ‘I denounce the system that denies my existence.’ Her vocal delivery is as startling as it is impassioned.

It was Poison Girls’ decision to relocate to Epping, taking up residence in Burleigh House (a licensed squat destined for demolition to make way for the M25), that brought the band into contact with Crass.

Neither band had been aware of the other’s work, but, by sheer coincidence, Poison Girls’ new base of operations was only around four miles from Crass’ home, Dial House. A meeting of minds quickly set in motion an intense period of close collaboration.

Poison Girls provided the funding that underpinned the launch of Crass Records, and in turn Crass re-released both Hex and Chappaquiddick Bridge on the Crass label.

It was a hugely positive association, from which both bands benefitted, and through shared projects, such as the celebrated, landmark Bloody Revolutions / Persons Unknown single, both bands together raised the profile and appeal of anarcho-punk.

Subversa’s rendition of the lyrics of Persons Unknown is remarkable, circling through the incisive, biting and sharply perceptive lyrics before intoning ‘flesh and blood is who we are; flesh and blood is what we are; flesh and blood is who we are; our cover is blown.’

Yet as both bands played more and more gigs together around the country, Poison Girls became concerned that Crass’s popularity was beginning to overshadow Poison Girls’ own.

Young women took inspiration from her feminism, her confidence and her reappropriation of the ideas of beauty and artistry

Subversa’s passion and commitment, which shines through so strongly in the band’s early work, became an immediate inspiration to many people in and around anarchist punk culture: her formative position within anarcho-punk culture help to define different expectations of gender and of generation, and to tear apart any puerile assumptions about the connections between rebelliousness and youth (and the correlation between age and conservatism).

Young women took inspiration from her feminism, her confidence and her reappropriation of the ideas of beauty and artistry.

The sheer variety of Poison Girls’ creative output was evident during their association with Crass, and throughout the distinctive timbre of Subversa’s vocal shone through.

From the edgy, unsettling drive of Ideologically Unsound to the swirling, captivating poetry of Promenade Immortelle, it was the quality of Subversa’s voice that did so much to shape the distinctive identity and give depth to the band’s rich and textured sound.

Poison Girls were always a strong collaborative project, but within that Vi Subversa was a decisive, distinctive voice who it was rarely wise to ignore. As the band’s profile rose, Poison Girls became concerned that their own identity risked being submerged beneath that of Crass’ own.

It was an oddly conflicted position – of being both too comfortable (of enjoying the increased pull that the association ensured) and uncomfortable (of being overshadowed by their partners) at the same time. Subversa spoke, with some evidence of a lack of diplomacy for which she and the band developed a reputation, that it would have been easy to have settled into becoming ‘Mrs Crass’.

The band’s first independent release, in this new period of independence, was a live recording of what was (apart form the ZigZag squat gig of late 1982) the band’s last shared bill with Crass. Total Exposure was an unadorned mixing desk representation of the band’s live sound, harsh, direct and unapologetic; with Subversa’s gravelled, edgy and compelling voice cutting through the songscape.

It showed Subversa at her most directly confrontational, showcasing songs like SS Snoopers (an excoriating condemnation of the invasive practice of DSS investigators), in which Subversa rails: ‘SS Snoopers. SS Spies. Buzzing round your body, like flies.’

On the recording, it’s possible to hear Subversa react to a young male punk who spat phlegm at her from the audience. ‘Rot in hell!’, she screams, in withering response. No prisoners taken.

The follow-up release could scarcely have been more different. Where’s the Pleasure? gave space not just for Poison Girls to return to the theme of the exploration of personal relationships but to give Subversa the opportunity to again explore the more tender, softer and warmer aspects of her vocal range and her delivery style.

Importantly, Where’s the Pleasure? saw a turning point in the band’s presentation of themselves as the group came out from behind the collective anonymity of banners and icons to reveal the group as ‘flesh and blood’.

Subversa’s was the most prominent image on the cover; and her face would appear, in powerfully reflective pose, on the front cover of the weekly music paper Sounds to illustrate a feature on the band’s appearance in Belfast. On her own terms, and that of the band, she was asserting control of her image and public identity.

Subversa remained an outsider and, like all good anarchists (and quite a few bad ones), resisted any attempts by others to pigeonhole and lockdown her identity or persona.

While, in parallel, the temper of Crass darkened, Poison Girls felt they had the mandate to move further away from the template of didactic, instrumental punk. While there were a number of different drivers pushing forward this process, there was a clear desire to move past the the simple presentation to male-dominated punk audiences, and to rethink again the idea of the format of the gig.

The aim was to sever the association with their monochrome, all-out-attack punk of their time with Crass, redefine the band’s identity and present a different, though equally immersive, experience.

Reconnecting with their theatrical roots, Poison Girls assembled a new type of touring ensemble, comprised of a variety of artists and performers (comedians, poets, ranters, and duos such as Akimbo and Toxic Shock), and headed back on tour determined to offer a completely different ethic and ethos to that of the punk gig.

It took the band away from the tension and high-stake confrontation of the anarchist punk gig and towards the unpredictable sensibilities, and the eclectic sounds and sights, of the nightclub.

Under interview, she demonstrated an impressive, articulate style, making her anarcha-feminist case with a natural confidence

The promotional work around the No Nukes Wargasm compilation benefit album (for which Poison Girls contributed a sublime orchestral reworking of Statement), saw Subversa pushed into a bright but brief media spotlight, and led to a number of radio appearances and newspaper features.

Under interview, she demonstrated an impressive, articulate style, making her anarcha-feminist case with a natural confidence. Whether joining the ‘Punk debate’ in Sounds, or appearing as a panelist on Midweek on BBC Radio 4, Subversa came across as fluent, convincing, empathic and authoritative.

If Penny Rimbaud of Crass could, on occasion, lose an audience in crisscrossing spirals of poetry, romanticism and existentialism, Subversa’s anarcha-feminism was always grounded, intelligible and locked into the practical realities of life.

But, to her frustration, much of this press coverage sought to focus on the ‘novelty’ of Subversa’s involvement with contemporary punk counter-culture rather than its substance. And having ‘run the story’ on the ‘punk Mum’, most outlets considered the job done.

This brief period of renewed press scrutiny did not mean that Poison Girls were able to secure ongoing media interest in the group’s work.

Poison Girls again shared the stage with Crass, and with many other bands in the anarcho-punk firmament at the celebrated London Zig-Zag squat gig in late 1982.

But relations between the two band broke down a year later following an explosive disagreement over an essay on the dynamic between the exploitation of animals and the oppression of women written by Subversa.

As anarcho band Conflict prepared their To a Nation of Animal Lovers single for release on the new Corpus Christi label set up by John Loder of Southern Studios, they commissioned Subversa to write a sleeve essay discussing the interplay of feminism and animal rights.

Subversa considered her options carefully. She could have authored a straightforward polemic, stressing the need for an anti-oppression politics that was all embracing: one that locked together the logic of feminism and of animal liberation.

Instead, she chose to ruffle feathers, and penned an intentionally provocative statement which challenged what she saw were the often-blinkered gender politics of many male animal rights activists; militants who ignored (and contributed) to the oppression and exclusion of women whilst championing the rights of other species.

The piece urged male listeners to reject the illusory protection of machismo, to accept their own vulnerability, and to embrace and cherish tenderness and love. It ended with a potent, and purposefully shocking, revenge fantasy, which declared:

do not be surprised if the rest of us rise up and turn against you.

We can invoke nightmares of revenge worse than you can imagine.

And the woman may rise up who will have her knife.

And in the name of life she will take up her knife,

and, castrating, will avenge even the the least laboratory rat

that, discarded, ends up in the tin of Pal

you may feed your pet tomorrow morning

Subversa was more than aware that the piece was, in anarcho-punk terms, politically incendiary.

As the new Corpus Christi label was, to coin a phrase, ‘semi-detached’ from Crass Records, both Conflict and Subversa assumed that decisions around the release were theirs to make.

When Penny Rimbaud of Crass caught sight of the proposed artwork, he was outraged. He insisted that the statement be removed from the sleeve, and he immediately severed all working relations with Poison Girls, sending all remaining record stocks round to Poison Girls’ house by taxi.

Loder demurred, and the single release went ahead with new artwork replacing Subversa’s essay. It was the ill-tempered low point in relations between the two bands, but it reflected Poison Girls’ determination to assert their own politics, even when doing so brought them into direct conflict with former anarchist associates.

It again also showed Subversa’s own implacable, awkward – and sometimes less than diplomatic – approach to the practice of politics. She and the band would not let the issue drop, and produced gig handouts containing the words of what Poison Girls’ dubbed The Offending Article.

Adopting an approach unlikely to heal the rift, the flyers announced that this was the text ‘Crass tried to ban.’ Once again, Subversa was untroubled by the experience of being ‘out of line’ with the views of those politically close to her.

That same sense of distance and otherness also shaped Subversa’s relationship with the resurgent British feminist movement; a progressive current she always remained a dissident member of.

She had little sense of affinity with the politics of ‘separatism’, and – despite the profile of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the culture of the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s – Subversa retained a critical distance from its ‘women only’ perspectives and its assertion of a ‘natural’ correlation between the ‘essence of womenkind’ and the embrace of peace.

Subversa also possessed a firm anarchist critique of those individual ‘professional feminists’ who secured personal career advancement through the offices of Labour Party and ‘municipal socialist’ local councils.

That same sense of distance and otherness also shaped Subversa’s relationship with the resurgent British feminist movement

While Crass disbanded in 1984, Poison Girls continued; not considering for a moment the idea of copying Crass’ ‘end of days’ dissolution. With their forays into the musical mainstream not delivering the hoped-for results, Poison Girls found themselves in a quandary.

Should they redouble their commercial efforts; reassert the band’s identity as DIY outsiders; or look for new ways to meld the two approaches? The band struggled to negotiate the tensions.

On one side came hard-to-resist offers to play lucrative gigs for the GLC; on the other was the desire to show solidarity with the Stonehenge festival goers attacked in the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985, an impulse which pulled the band back in the direction of the counter-culture.

Poison Girls’ most well-received single release of this period was the riotous, celebratory I’m Not a Real Woman.

As well as its brilliantly mocking lyrics, the front cover of the single brilliantly captured the joyous image of Subversa as a can-can dancer, grinning with defiance and abandon, gleefully upsetting the expectations of age and gender, and daring the viewer and listener to object.

The band began a short but concerted attempt to break through to commercial success and more mainstream accessibility, releasing two consciously radio-friendly singles: One Good Reason and Are You Happy Now?

In the presentation of both songs, the subversive message was more subtle and a smoothness in production took away some of the tougher, spikier edges in Poison Girls’ sound. The singles simply did not showcase the quality of Subversa’s vocal style to most compelling effect. The work was witty and clever, but it lack the archness, the acidity and the biting edge of the Poison Girls of old.

The band undercover incursion into the pop mainstream did not deliver much in the way of commercial or artistic dividends; and Poison Girls once again found themselves as cultural outsiders.

The post-Miners’ Strike album Songs of Praise saw the tensions between the band’s outsider identity, and its continuing efforts to secure wider artistic and commercial recognition return, writ large. Here though, the richness and edginess of Subversa’s voice was again given freer reign, to satisfying effect.

The sense of melancholy and of political frustration found in the lyrics of many of the album’s songs was perfectly reflected in Subversa’s vocal delivery; there is a recurring sense of sadness, but not of defeat.

Though now without a record contract, Poison Girls continued to play live extensively and crafted a new set of songs that they never had the opportunity to record.

As the band toured Europe, they were able to cement their reputation as a formidable live act, and built a strong and resilient following. Freed from the weight of anarcho-punk expectation, the band were able to experiment and to thrive.

But it was not enough to sustain the band in the long term. The band continued to tour in the UK and beyond, before agreeing that the time had come to call it a day in 1989.

Subversa continued to work with Richard Famous, on projects including Aids: The Musical, but her creative and political outputs became more occasional as she enjoy a period of semi-retirement.

Subversa continued to enjoy huge amounts of support and affection in and around the anarchist punk diaspora, playing a 60th birthday gig (at which relations with former members of Crass were rekindled).

In 1994, Subversa moved to Spain and settled into a comfortable and well-appointed casa, spending much of her time on two of her favourite activities: making music and gardening.

Several obituaries picked up on an anecdote outlined by Penny Rimbaud of Crass, which described how Subversa was injured in Spain when she fell victim to rogue builders who carried out botched repairs on her casa – which then collapsed, with her inside, injuring her badly. Rimbaud recounted how this soured Subversa’s Spanish experience, and led to her returning home, deflated, shortly after.

Several members of Subversa’s family have objected to this story; and not just because of its factual inaccuracies, but because it paints Subversa as an unwitting victim of ‘cowboy’ contractors, and someone whose poor choices led her to return home defeated by the experience.

In fact, it was not the builders working on the extension to the house who weakened the fabric of the casa (who were well-regarded local craftsmen, hired by Subversa); it was the original construction of the property that made the building vulnerable. After the cave-in of the roof, Subversa recovered from the injury to her leg, repaired and sold the house, and arranged for another residence to be built nearby, which caught more of the sun.

Continue reading “Vi Subversa and Poison Girls: The Hippies Now Wear Black – Rich Cross”