Deprivation of Existence: The Use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria.

A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds. (illustrations and more details from Report added)

This post is also available in: Arabic October 9, 2020, 505 views

To read the full report (121 pages) in PDF format, please click here.

To read the original post, with references etc click HERE

….2. Executive Summary

24 June 2020 marked the 46th anniversary of one of the large-scale projects aimed at bringing about demographic changes, which have been in the planning since before 2011. This was also the day the National Command of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party passed resolution No. 521 in 1974, which provided for the effective implementation of what was termed the ‘Arab Belt’ project.

At that point, thousands of Arab families who lost their homes to the creation of Lake Assad, were prompted to move and settle in ‘model villages’, that were built on lands seized earlier under the Agrarian Reform Laws, starting with Act No.161 of 1958, the year of the establishment of the unity between Syria and Egypt.

_________________

…… The ‘Arab Belt’ project recalls Erdogan’s settlement plan of 2019

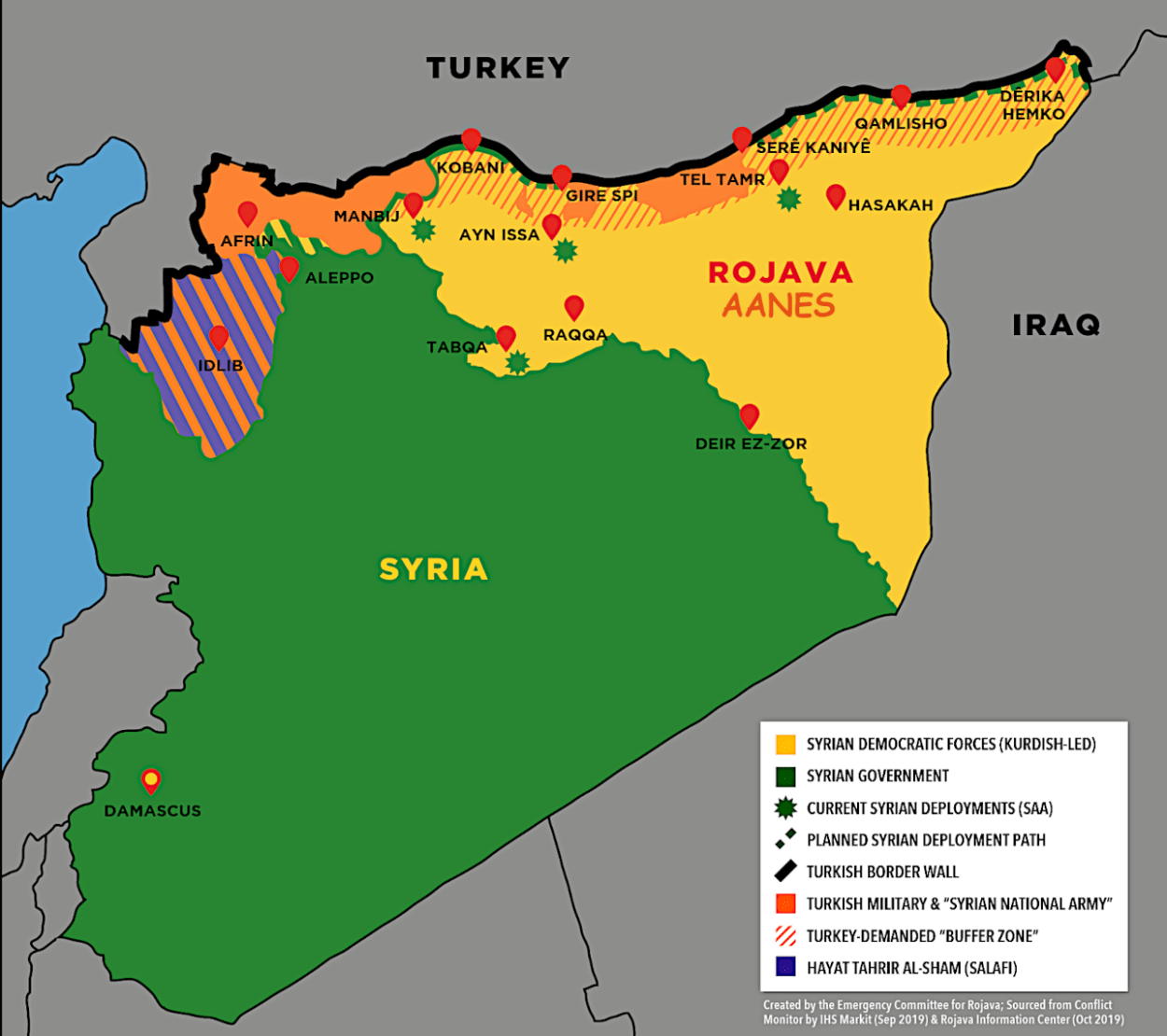

In one of its aspects, the ‘Arab Belt’ project resembles Turkey’s plan to resettle millions of Syrian refugees to northeast Syria, historically inhabited by the Kurds.

Image no. (13) – Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan pointing to the area between Serê Kaniyê/Ras al-Ayn and Tell Abyad on map during an interview on Turkey’s state-run TRT news network, aired on 24 October 2019.84….

This plan, which was submitted to the UN in November 2019, was put on the table following Operation Peace Spring, that resulted in Turkey’s occupation of Syrian lands in the north.President Erdogan himself has stated that, because of its geological features and the fact that it was desertic, the occupied area was designed for Arabs, and not Kurds.83…….

_________________

Towards the promotion of Arab nationalism at the expense of the Kurdish identity in Syria; as described by international human rights organizations, the Syrian Arabs were transferred by government to settle in the Kurds’ home areas with the aim of establishing the ‘Arab Belt’ along the length of the border strip with Turkey, which meant to separate the Kurds of Syria from those of Turkey and Iraq.

The planned demographic change also included deporting the Kurds residing in villages within the scope of this ‘Belt’ to other areas.[1]

Contrary to what is commonly said, it seems that the memorandum submitted by Muhammad Kurd Ali, Minister of Education in Taj al-Din al-Hasani’s first government,[2] to the heads of ministries, dated 18 November 1931, was one of the first official recommendations, which explicitly called for the deportation of the Syrian Kurds from their areas along the northern borders for national reasons.

Talking about the situation of al-Hasakah province (then called Jazira), Kurd Ali referred to the migration of Kurds, Syrians, Armenians, Arabs and Jews to the border area adjacent to Turkey, saying that the Kurds, who were the largest in number, should be displaced to areas far from the borders of Kurdistan, proposing to grant them lands around Homs and Aleppo and to integrate them with the Arabs there.[3]

Also, in the context of the initial application of the Arabisation policy, the Central National Government appointed in late January 1937, Emir Bahjat al-Shihabi, who manned the military administration during the period of the Arab government, as a governor of al-Hasakah. Al-Shihabi came with a plan in his pocket, which he quickly launched. That plan aimed to ‘cleanse’ the small government administration of local employees from the Syriacs and Armenians, affiliated with the previous regime, and recruit new staff from the Arabs of Aleppo.[4]

Since the Ottoman era at least and until the declaration of Agrarian Reform Law No. 161 on 11 June 1958, the form of ownership throughout present-day Syria was feudal, as large areas were in the hands of a few people who were mostly notables, sheikhs of clans and princes.[5]

Law No. 161 determined the maximum admissible land ownership and provided for the confiscate of excess areas. However, the implementation of the law in al-Hasakah, specifically in areas historically inhabited by the Kurds, count on political considerations; this was illustrated in the projects carried out in the following years, which consisted of arbitrary seizing of properties, especially that of Kurds, and giving them to Arabs of clans who lived in the vicinity and/or to those who were later transferred from other Syrian regions.

Building Autonomy Through Ecology in Rojava

By looking at the facts and events which followed the unity between Syria and Egypt in 1958, one can tell that the first building block for the demographic changes in areas of northern al-Hasakah province, western Tell Abyad town, Raqqa province, and Afrin region in Aleppo province, was laid at the stage of establishing the United Arab Republic (UAR).

In the political period that was named by historians as the ‘separation era’, specifically in 1962, a special census was conducted in the province of al-Hasakah, whereby tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds were stripped of their nationalities, which resulted in:

- Impossibility of proving ownership of lands which belong to persons rendered stateless.

- Kurdish peasants who lost their nationality not entitled to lands distributed according to Law No. 161 and its subsequent amendments.[6]

In parallel, successive Syrian governments focused on suppressing the Kurdish identity, by restricting the overt use of the Kurdish language in schools and/or in the workplace, with the prohibition of publications in the Kurdish language, and the celebrations of Kurdish holidays, such as Nowruz, for decades.

This was led to the Kurds in Syria being subjected to serious human rights violations, just like other Syrians, but, as a minority group they suffered identity discrimination.[7]

Women struggle for a new society in Rojava

The ‘Arab Belt’ project was effectively implemented in the 1970s. That belt stretches in a length estimated at 300 kilometres along the Turkey-Syria border strip (starting from the far northeast of the Dêrik/al-Malikiyah district to the administrative borders with Raqqa province, west of the Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê), with a depth of 15 kilometres at its innermost point.

Thus, about 4000 families from the Arab tribes in the countryside of Raqqa and Aleppo – especially from villages flooded with water that gathered behind the Euphrates Dam/Tabqa Dam – were transferred and settled in model villages within the belt.

That was done under the banner ‘building the new society’ uttered by the late Syrian president Hafez al-Assad in a speech he gave at the opening of the dam, addressed to the people of al-Ghamr area, [8] and others who will start a new life in the Euphrates basin.[9]

An ad hoc committee was established for the implementation of the ‘Arab Belt’; it was called ‘al-Ghamr Committe’ by the Ba’ath Party. One of the goals of this commission was to induce the Arab tribes in the flooded area to move to the new housing areas.

For the completion of the plan, security and executive authorities were ordered to prepare the ground in al-Hasakah, thus, visits to representatives of these clans were organized throughout a whole year, in order to inform them of the areas where they were to be settled and the land they would invest.[10]

The al-Ghamr Arabs refused to bury their dead in their new residential areas, but rather moved them to Raqqa until the early 1980s. Further, quite a few of them refused to build mosques without the approval of the original owners of the land, while others refused to use the siezed lands income to travel to Hajj, without the consent of the original owners. This indicates that the Arab tribes rejected this plan.

Besides its political aims and disastrous effects – especially social ones – the ‘Arab Belt’ project constitutes a flagrant violation of Syrian laws themselves; the permanent Syrian constitution of 1973, under which the bulk of the project was implemented, provided in its article 15:[11]

PDF) Assessing International Law on Self-Determination…

Private ownership shall not be removed except:

- In the public interest by a decree;

- Against fair compensation;

However, neither of the two conditions were met in the implementation of the ‘Arab Belt’ project, as the expropriation was for the benefit of other Syrian citizens, who are different only in terms of language and nationalism.

Moreover, this policy, which has been pursued by successive governments of Syria, violates the principle of equality between citizens in rights and duties, in accordance with Article 25 of the 1973 permanent constitution.[12] As removing ownerships from Syrian Kurds and granting it to Syrian Arabs without any legal justification or court ruling, is a clear discrimination and favouritism. This policy also violates Article 771 of the Syrian Civil Code promulgated by Legislative Decree No. 84 of 1949, which affirmed that no one may be deprived of his property except in cases determined by law, and in return for fair compensation.…….

Afrin Region

……..In the Afrin region, the Agrarian Reform Law chiefly targeted the lands of the Juma Plain (Deşta Cûmê), considered the region’s most fertile plot and its preliminary economic reservoir. Spreading across these plains, the larger parts of the confiscated and then re-distributed lands belonged to Aghas.122 The beneficiaries, however, were members of Arab tribes, who arrived in Afrin either as settlers, laborers or farmers, while only 20% of the Kurds benefited from the process of redistribution……

…….Later, during the 1970s, the Syrian government established another set of residential compounds, in conjunction with the launching of the ‘Arab Belt’ in al-Hasakah. These compounds were also handed over to Arab settlers, in a step similar to that carried out in the Jazira region, including the Bakhashi compound — located between the two vil-lages of Nazan and Hasan Dairli, at the crossroads leading to Nabi Hori, Bulbul and Midanki….

7. Local Repudiation and Resistance of the Authorities’ Repeated Attempts at Demographic Change

In his account, Abdulhakim Mulla Ramadan,125 born in 1943 in the village of Robariya, rural Dêrik/al-Malikiyah, reminisces about forms of local resistance. They engaged in skirmishes with the security forces repeatedly under the rule of the 1961 government, that attempted to put into practice the land seizure started by the UAR government:

“For years, we first resisted the decisions providing for the confiscation of our lands, and second the attempts at handing them over to other people. We did not stop plough-ing the lands or cultivation, even though the government would show up every time and confiscate the yield.

We were arrested and imprisoned due to our resistance till the 1970s, when the government brought the al-Ghamr, the Arabs affected by flood-ing, into the area, forcibly ploughed our lands and ultimately seized large plots of them.” The witness was interviewed in person by STJ’s field researcher on 7 December 2018.

In 1967, the Syrian authorities embarked on the confiscation of new lands that belonged to Kurdish clans scattered across the Jazira region.

As a result, Kurdish villages became a site of confrontations with the police and security forces supported by the Hajana, Bor-der Guard. The people protested the displacement plans.

An uprising, thus, starting from the village of Ali Farow, west of Qamishli/Qamishlo, up to al-Jarah River in the east, broke out, leading to hundreds of Kurdish peasants being arrested, insulted and subjected to torture for their stand on the matter.126

The resistance to the land-seizure project in the village of Ali Farow in the city of Amu-da is perhaps the most prominent incident in this context. This prompted the French newspaper Le Monde to publish a news report covering it in May 1967, after the government seized measures of the village’s lands and labeled them as ‘State Farms’.

Collective-ly, a group of peasants, affiliated with the Kurdish Leftist Party and several communists, decided to plough the already cultivated lands themselves in April 1967.

Enraged by their act, the then Director of the district of Amuda, First Lieutenant Yousef Tahttouh, dispatched a police force to stop them that ended up challenged by the people. In retaliation, Tahttouh reported to higher ranks that “an armed Barazani-urged revolution was taking place in Ali Farow”.

Consequently, on the night of 1 May 1967, the governor mobilized a force of 35 different military vehicles loaded with soldiers and police, about 500 personnel, who surrounded the village. Sticks and stones, the villager’s only weapon, could not survive that military force, and they finally surrendered.

The force then looted the village, and arrested more than 133 people from the village and its surroundings, who were next transferred to the Qamishli prison.

As it failed to accommodate all of them, they were transferred to al-Hasakah prison.127

In fact, the resistance against displacement and land confiscation the Kurdish people embarked on did not amount to an organized movement throughout their regions. They were rather instances of resistance in separate Kurdish areas.

….Bashar al-Assad following in his Father’s Footsteps

Two decades into the ‘Arab Belt’ project, the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Re-form issued the Letter No. 1682/MD on 3 February 2007, which provided for resuming the redistribution of the lands labeled as ‘State Farms’.

Indeed, on 8 June 2007, the Ag-riculture Provincial Directorate sealed contracts under which 5.600 hectares of the lands in Kharab Rushik, Karirush, Kerkimiro, Qadirbaik, and Qazar Jub, rural Dêrik/al-Malikiyah, were granted to 150 Arab Families in the al-Shadadi region, south of al-Hasakah.

The provisions of the letter were met, even though the Regional Command had passed Resolution No. (83) in February 2000, ordering the liquidation of the ‘State Farms’ and the redistribution of the lands they encompassed to a prioritized list of the employees who worked at the departments of the ‘State Farms’.

Back then, the Defend International Organization launched a campaign: “Against any Ethnic Belts in the Middle East: The Ethnic Belt in al-Hasakah and Dêrik”. The cam-paign addressed the European Union (EU) and the United Nations (UN) to press the Syrian authorities to cancel the resolution, to refrain from passing such similar resolutions and to stop the implementation of the ‘Ethnic Belt’ plan in the al-Hasakah prov-ince.

It also demanded that the state distribute lands impartially to the region’s people, treat all citizens equally and without any forms of discrimination, as well as to allow all minorities within the Syrian borders to register their ownership over properties under their own names.

17.Conclusion

Since the 1930s, successive governments in Syria contributed to an integrated system of racist ideas that worked against the formation of a state in which the society’s various ethnic components are well integrated and enjoy equality.

This provoked social divisions cooked systematically by the Ba’ath party since seizing power in 1963 through demographic change projects, including the ‘Arab Belt’, which was initially met with little resistance from the al-Ghamr Arabs and later gained growing acceptance from a cross-section of the Syrian people, among them elites and opponents who did nothing to prevent its implementation, and even ignored it completely in their literature and political programs, citing that it was a matter for the Kurds alone.

The Syrian opposition, represented by the Coalition and its political and military arms (the Syrian Interim Government and the National Army), legalized the seizure of the Kurds’ property in areas occupied recently by Turkey in Afrin, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad, as verified by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic and other international organizations.*

. That led to the disintegration of the Syrian people into sub-statist structures and impeded the draft of an inclusive political project, which can ensure genuine equality of rights for all to reach the hoped-for state of citizenship………/…..p 119

3. Recommendations

Property restitution should be viewed and implemented in the light of the current political process in Syria, since that will have political and fateful dimensions that will positively affect millions of Syrians. The success of this process will contribute to the success of Syria’s peace process, which will provide a safe and neutral environment and will encourage Syrians to participate in public life, especially in elections, and will also build confidence in the constitution that can be drawn up later. Therefore, STJ would like to address recommendations:

A. To the United Nations (UN)

- To ensure inclusiveness, fair and genuine representation of all Syrians – regardless of their affiliations – in all political negotiations, especially those related to the Syrian constitution, to assure that all issues of individuals and the groups to which they belong are included……

………C. To actors in the Syrian conflict (the United States – the European Union – the Arab League – the Russian Federation – the United Kingdom)

- To ensure the prohibition of current and future discriminatory projects that are taken against the Kurds or other groups of Syrian people in any part of Syrian.

- To determine the dimensions of the Turkish plan aiming at demographic changes in the Syrian territories it occupied along the northern border strip, and to ensure that projects help in this are not funded.

- To ensure the return of all forcibly displaced people from Afrin, Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and all other Syrian regions, to their homes, and also to ensure the return of expropriated property to its original owners, and the accountability for all those involved in human rights violations.

- To work to restore Syrian citizenship to those who have been stripped of it under the extraordinary census of 1962.

D. To owners of expropriated property

- To keep the originals of all court decisions and any other documents proving ownership in a safe place.

- To keep copies of all documentation with a reliable, honest and known third party if necessary.

E. To the current Syrian government and/or future governments

To form a neutral, independent and impartial Syrian national committee to study how to end the so called the ‘Arab Belt’ project and other similar discriminatory projects which resulted in the seizure of people’s property, and also to study the ownership documents submitted by claimants, and decide their cases fairly and expeditiously, provided that the decisions of the aforementioned committee are subject to appeal before the competent courts in accordance with the Syrian laws, and that all results are published in full transparency in the public and in official newspapers.

To entitle any formed committee to study both; the issue of the landowners who were deprived from their lands and that of people whose lands were flooded and thus transferred to Jazira – we actually see them as victims of the racist project conducted by the Ba’ath government – and to ensure fair compensation for all.

To not to neglect the social dimensions of discriminatory projects on any Syrian component, and to work seriously to make real reconciliations between all parties, as well as looking forward to building a peaceful future which ensures full equality of rights and duties in Syria………….

To read the full post, with references etc click HERE

To read the full report (121 pages) in PDF format, please click here.

To read post in Arabic Click HERE

Related posts

Ethnic Cleansing In Syria: The Unseen Terror In 1960, the Syrian government issued a decree that denied the Kurds the right … The Assad regime is employing pan-Arab nationalism in northern Syria to …

ETHNIC CLEANSING ON A HISTORIC SCALE: – ReliefWebreliefweb.int › reliefweb.int › files › resources PDFEthnic cleansing on a historic scale. The Islamic State’s systematic targeting of minorities in northern Iraq. Amnesty International September 2014. Index: MDE …

Comment

Severe discrimination against Kurdish people and other minorities is still rife both in the Assad regime and the general population. Kurds are thought of like black people were in the USA 50 years ago. For example in the Astana peace negotiations which include Iran, Turkey and many groups of their mercenaries, the Kurds and the AANES Rojava administration are SIMPLY EXCLUDED COMPLETELY. The Assad regime would rather cosy up to Turkey (which to this day is ferrying armaments into Idlib and occupying Afrin, Azaz, etc and the ‘Turkish Belt’ in the NE) rather than even speak to 20% of Syrian citizens who happen to be Kurds. …thefreeonline