”I started by reading a whole mess of utopias and learning something about pacifism and Gandhi and nonviolent resistance. This led me to the nonviolent anarchist writers such as Peter Kropotkin and Paul Goodman. With them I felt a great, immediate affinity. They made sense to me in the way Lao Tzu did. They enabled me to think about war, peace, politics, how we govern one another and ourselves, the value of failure, and the strength of what is weak.

So, when I realised that nobody had yet written an anarchist utopia, I finally began to see what my book might be. And I found that its principal character, whom I’d first glimpsed in the original misbegotten story, was alive and well—my guide to Anarres. [4]”

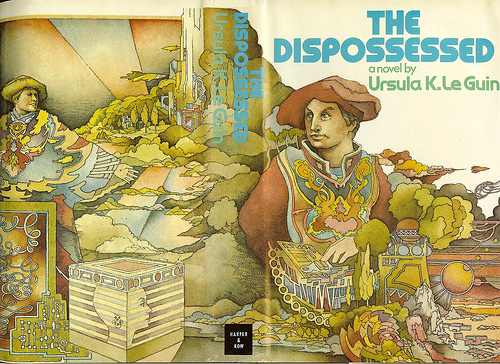

EM: The Dispossessed is one of your most well-known works. Was there any novel which explored anarchism so explicitly before then?

UG: I don’t think so. That’s one of the reasons I thought of writing it. I’d been educating myself about pacifist anarchism for a year or more. I started reading the non-violence texts—Ghandi, Martin Luther King and so on—just educating myself about non-violence, and I think that probably led me to Kropotkin and that lot, and I got fascinated. Portland used to have a hundred independent bookstores, and one of them was rather political, and in the back room, if he knew you, he would take you in to see his anarchist stuff.

EM: When would this have been?

UG: When was that book? The early 80s? Late 70s? That store had some wonderful stuff, which at the time was very hard to find. Not so much anymore. And of course I found out about some of the modern anarchist writers. I was excited following that up. And then at the same time I was reading utopias. And there was a utopia for every political thing you could think of, but not for anarchism. Isn’t that odd? Well maybe I should write one. So then I had to re-read and read things to plan how on Earth would you organize an anarchist society, which was a lot of fun, but difficult.

EM: Especially on the scale of a world.

UG: Even a very thinly populated planet, there’s a lot of people to organize.

EM: You said in an essay that a Utopia, with a capital U, should be a practical alternative. That really struck me.

UG: I’d have to think about that. In my own mind I’ve moved on quite far from the utopia of The Dispossessed to the semi-utopia of Always Coming Home, where I did try to make it simply a lifestyle. There was no political basis at all, in the sense of European or large nation politics, therefore people think that I was trying to idolize the American Indians or something.

What I took from the Indians was, essentially, running your lives without a central government and using consensus as the basic mode, which you can’t do in a big society, it’s a matter of numbers. But I wanted to think out what it might be like. I think the lack of politics, for some of the readers, makes them think that it must be primitivist, and it ain’t necessarily so.

EM: It’s been influential in bringing the dialogue into the mainstream.

UG: Yeah. Writing a serious utopian novel that is an anarchist novel. It hadn’t been done, and there were hardly any anarchist texts that weren’t non-fiction, so just having a big fiction work that’s all about anarchists, I think made quite a difference.

EM: Especially with things like gender-neutral pronouns. It’s a conversation that’s been happening for a while, but is getting louder now. It shows how important linguistics is.

UG: Oh gosh yes. When you start looking for languages which have a gender neutral common pronoun, what have you got? Some kinds of Japanese and Finnish… I believe Finnish is gender neutral, which is cool. So translating The Left Hand of Darkness is a cinch for them.

The Dispossessed. Ursula Le Guin’s anarchist utopia…Free Download HERE:

The New Utopian Politics of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed or

Listen to Thye Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin at Audiobooks.com

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution.”

— Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed.